Alex Beattie

A Temporal Sense of Place

The Politics of Attention and Information Architecture

Abstract

The paper [1] introduces perspectives on power/knowledge and technicity to politicize the design and architecture of digital, cross-channel or hybrid places. It applies these concepts to update and revitalize Doreen Massey’s concept of place, to argue that digital places appropriate the attention of inhabitants to create a temporal sense of place. This is extrapolated from two contrasting case studies of digital place: a social networking service and a content platform, to demonstrate how various forms of economic, cultural and social value can be generated. This re-conceptualization of place is critically applied to the information architecture theory of place-making to argue that information architects are active participants in the politics of attention within digital environments. It responds to the discipline’s awareness of its inherent political agency and offers two suggestions for information architects to design as change agents: (1) create place that necessitates affordances of temporal agency; (2) generate a holistic range of values in place.

Introduction

“Architecture is a political act by nature. It has to do with the relationship between people and how they decide to change their conditions of living” – Lebbeus Woods (Manaugh 2007)

The political dimensions to architecture may be contentious, but at least there is a debate. In contrast, information architecture has largely avoided political interrogation, perhaps due to its brief scholarly history, and origins in traditionally depoliticized disciplines such as library science, cognitive science and systems design. Yet several prominent information architecture practitioners and scholars are alert to the potential politics of their profession. Arango (2011 p. 47) acknowledges the power inherent in defining terms and taxonomies, asking for practitioners to be “increasingly proactive in our role as agents of cultural and political change”. Hinton (2015, p. 273) acknowledges the political aspect of place-making as artefacts are never neutral: “place-making can reify choices, values and agendas…we need to be aware of that agenda.” Most recently, Resmini (2016) calls for an enquiry into the political and ethical impacts of architecting seamlessly blended physical and digital places, labeling invisible architectures as “black-boxes”.

The aim of this paper is to politicize information architecture, specifically the practice of ‘place-making’. It draws upon political economy of communication, social construction of technology and post-phenomenological theory, and builds upon specific reflections on the politics of place, the power inherent to architecture and the agency of inhabitants within digital environments. The first of these is Doreen Massey, who articulated a spatial based politics for analogue places in the 1990s, when different parts of the world were ‘speeding up’ by experiencing ‘time/space compression’, or specifically globalization. Today, the world is again ‘speeding’ up. A new variation of time/space compression is occurring, currently brought about by the proliferation of digital information communication technologies (ICTs) and ubiquitous computing. Access to information is only a ‘Google’ away, and a myriad of connective opportunities are offered by social media sites such as Facebook or digital ICTs such as Skype. Access to these digital services appears to be free as users ‘pay’ with their data, or more significantly by consenting to allow service providers to use their data as proprietary goods to trade with other parties. While Massey was interested in the politics of accessing certain places, the issue of interest today concerns what inhabitants of digital places trade to have free access [2].

To refurbish Massey’s politics of place for place-making, requires an examination of the power-relations vested in architecture, and to this end, the second theoretician discussed is sociologist Michel Foucault. To further narrow the specific power-relations to information or digital architecture, the third theoretician discussed here is Gilbert Simondon, whose concept of technicity enables a closer examination on the temporal agencies afforded in artificially-created environments. In sum, it is argued that place-making is a technology of power, and once architected and designed, digital/physical, or blended spaces (Benyon 2014) modulate an orientation in time. That is, a temporal sense of place.

This new understanding of place is explored more intimately with application to two distinct cases of digital places: the social media platform Facebook, and the content platform AfroFuturist Affair (AFA). These represent contrasting scenarios in which the content and architectures of a blended space are deployed to orient inhabitants’ attention in order to create value. The size and context of each digital place varies, ranging from Facebook’s ecosystem of digital services, to AFA’s niche cross-channel products. Concluding this I articulate a politics of attention and how a revitalized concept of place impacts on the theory of place-making in information architecture. I offer a critical perspective on place-making with two suggestions for information architects to design as change agents: (1) create place that necessitates affordances of temporal agency; (2) generate a holistic range of values in place.

Revitalizing Massey’s Concept of Place

Doreen Massey was a radical geographer, feminist and political activist who died in 2016, at the age of 72. In 1991, Massey wrote her seminal text, a brief eight page paper titled A Global Sense of Place. Here she conceived of a politics of place as spatially based, and considered globalization a privilege for those with access to newer ICTs (which at the time were the fax or telephone) and mobility (such as air-based travel) in comparison to those without it. In the paper she details a vivid and novelistic description of this type of politics, deliberately placing the reader in an omnipresent seeing position, knowledgeable to all movement in the world:

Imagine for a moment that you are on a satellite, further out and beyond all actual satellites; you can see ‘planet earth’ from a distance and, unusually for someone with only peaceful intentions, you are equipped with the kind of technology which allows you to see the colours of people’s eyes and the numbers on their number plates. You can see all the movement and tune in to all the communication that is going on. Furthest out are the satellites, then aeroplanes, the long haul between London and Tokyo and the hop from San Salvador to Guatemala City. Some of this is people moving, some of it is physical trade, some is media broadcasting. There are faxes, e-mail, film-distribution networks, financial flows and transactions. Look in closer and there are ships and trains, steam trains slogging laboriously up hills somewhere in Asia. Look in closer still and there are lorries and cars and buses, and on down further, somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, there’s a woman - amongst many women - on foot, who still spends hours a day collecting water.

Here Massey’s foremost point was to note that some inhabitants of the ‘global place’ can move freely, or at great speed, while others only with restricted movement or very slowly. It is about “power in relation to the flows and the movement” (Massey (1991, p. 26) or the relationships between different social groups and their relative mobility, which in turn depends on an array of social, cultural and economic factors. To analogise, Massey’s politics of place is akin to the politics of a popular but oversubscribed nightclub. Not everyone can get in, with each patron’s access depending on outward qualities such as gender and ethnicity, or the capacity to pay the cover charge. Furthermore, one patron’s access denies access to another.

While Massey correctly identifies her politics as relational, her analysis is limited by her preoccupation as a geographer of space. This spatial focus is too narrow for understanding power in information environments dense with blended spaces. While both analogue and digital places are subjective constructs combining landscapes, people, and natural, analogue or technical objects, digital places are in addition, distinctly artificial environments with the potential of being ambient. The intention here is not to return to Cartesian dualism, but to highlight a key difference of agency; while an individual is likely to be aware of their presence in an analogue place (because they are physically there), this cannot be presumed in digital places. Digital places represent complex assemblages of logics, concepts and technical objects and are riddled with defaults, or system presets (Kelly 2009) which requires deeper questions to be asked about the responsibility of designing base digital experience. Take for example TripAdvisor, a platform for curating tourist information, which connects businesses such as restaurants to potential patrons within its ecosystem. Neither restaurants who receive reviews or a potential patron who is nudged to visit via a notification, may be aware of their presence or others in TripAdvisor’s ecosystem. Some may consider the onus is on the individual to manage their digital presence (e.g., turn off their notifications), but this is a superficial understanding of power and a legacy of rational choice theory, proliferated by ‘liberal’ political science and economics institutions (Crawford 2016). In other words, it is applying a dated and analogue perspective to a covert digital problem.

What appears to be required is both a deeper and broader understanding of power, beyond its mere movement, and including its origins, manifestations, outcomes and psychological effects. To return to the nightclub analogy, not only are we interested in who can access the club, but the patron’s experience of that place, as well as why they are interested in attending in the first place. Our interests are less in their spatial access, but more related to their agency leading to, and within that place. A cliché associated with night clubbers is to show ‘pseudo-concern’ the following day about “where the time went”. An appropriate perspective of power should aim to interrogate this blank statement, and question whether agency within place stops at the individual. To refurbish Massey’s concept of place for information architecture necessitates a broader conception of power that will serve to unmask its inner workings. Therefore, the first step in revitalizing Massey’s conception of place is to update her conception of power.

Power/knowledge

One of the most original theoreticians of power was sociologist Michel Foucault. His view was that power is omnipresent and congealed with knowledge, and can be used for productive purposes. In this sense, Foucault belongs in the nurture camp. He would argue that parenting methods are a form of power, manifesting in specific types of knowledge about discipline, peer support and pastoral care. Parents embed their worldviews and values into their children to mold them into adults. Conversely, children are vehicles of this power who will subconsciously channel it for future use, in conventional wisdom they share with friends, and much later, in their own knowledge when becoming parents. Power is something imprinted into objects we interact with, and an objectification of knowledge.

Foucault did however, have much to say about the oppressive potential of power/knowledge. In “Discipline & Society”, he famously cited Jeremy Bentham’s model prison, the Panopticon, a schematic in which all inmates are unknowingly observed by a single watchman, to describe the essence of the disciplinary society. Foucault (1991 [1976]) considered the architecture of the Panopticon to be a technology of power that subjects individuals to an institutional gaze, which in turn coerces their behavior.

A Foucauldian perspective on power therefore appears as a suitable match to information architecture which as a practice actively constructs place or knowledge environments with the aim to enable user understanding. It points to the power in place-making, its ubiquity and impact in shaping views, digital experiences and norms. From this it is possible to assert that place-making subjects users to the gaze of third parties (such as advertisers), softly shaping their behavior, for either dominant (consumption) or productive purposes (understanding). This provides insight into the agency of the inhabitants of place, who consciously or otherwise consent to such power via normative practices, such as participating in socialized activities or without knowledge of the guise of power itself, and raises questions about the social practices that inform people’s understanding of specific digital places. Similar to the algorithms and architectures that govern digital places, power recedes into the background away from the eyes of users while inscribing a gaze itself. Despite Massey’s plea for a progressive and outward sense of place, this idea of progression is not easily discoverable in places which entrench norms while shading views that are critical of the very place users inhabit. Similar to a broadcaster unwilling to air a story about its television ratings, this raises concerns about the critical capabilities of inhabitants in increasingly persuasive places.

However, Foucault was a complex and often contradictory thinker and may have had reservations about this preliminary conclusion. While Foucault pre-dated information architecture, he did consider the limitations of architecture’s power to influence. In a 1982 interview with Paul Rabinow (1991, pp. 247-248), Foucault stated that

the architect has no power over me. If I want to tear down or change a house he built for me, put up new partitions, add a chimney, the architect has no control. So the architect should be placed in another category – which is not to say that is not totally foreign to the organization, the implementation, and all the techniques of power that are exercised in a society. I would say that one must take him – his mentality, his attitude – into account as well as his projects, in order to understand a certain number of the techniques of power that are invested in architecture, but he is not comparable to a doctor, a priest, a psychiatrist, or a prison warden.

Foucault’s summary of the power of the architect may be overstated and a reflection of his turn from studying power/knowledge to the scientific management of human beings [3]. Moreover, extending Foucault’s reasoning to information architecture and place-making to come to a similar conclusion is premature. When discussing Bentham’s Panopticon, Foucault theorized an analogue power structure which inhabitants experience by virtue of existing. The investment for inhabitants of digital places appears to be different, most notably the psychological cost of operating in increasingly pervasive digital environments. While the psychological implications of what architects design may be debatable (Leach 2009), they are more overt in information architecture. Architects predominantly create structures for habitation while the primary task of information architects is to create structures for understanding (Arango 2011). In a time of proliferated smart devices and an increasing number of digital artefacts enveloping the physical world, individuals cannot step out of or easily adjust digital environments as they can in physical buildings or rooms. In other words, opting-out requires knowledge that one is ‘in’. Greenfield (2006) considers the ability to opt-out as a paramount ethical issue in ubiquitous computing environments. Furthermore, while architects design with brick and mortar, information architects do so with digital information, which at its granularity are binary ones and zeroes. In a text about the increasing role of non-human agents in digital environments, Fogg (2001) warns of the persuasiveness of binary-oriented machines which are void of empathy or the capacity to tire, which we come to expect in human interactions. It is therefore necessary to reconsider Foucault’s comments in light of an evolved design practice bearing much greater psychological burden where its users have far less agency to craft their environments to their choosing. Therefore, the second step in updating Massey’s conception of place is, to discuss the psychological cost of operating in increasingly hyper-mediated environments.

The Technicity of Digital Places

Understanding the psychology of inhabiting a digital place requires an ontological enquiry into the nature of a digital place [4]. Critical to an ontology of digital places is technicity. Technicity represents the elements within digital objects and is a concept developed by philosopher Gilbert Simondon (2016 [1958]) to describe the ontology or the mode of existence of technical objects. Technicity draws attention to the digital milieu or possible interaction with a technical or digital object, as opposed to the substance of the actual object (Hui 2012). Importantly, technicity allows a recursive procedure to occur, in that “technicity is not exhausted in objects and is not entirely contained in them either” (Simondon 2016 [1958], p. 163). This reflects an observation by information architecture scholar Maggi (2014, p. 89) that digital places afford for “something to be acted upon”.

The significance of technicity is that it offers an explanation for how digital places appropriate users’ attention. Bucher (2012, p. 3) conceptualizes ‘technicity of attention’ to argue that attention is not merely a cognitive property but also “rooted in and constrained by the medium itself”. In a theoretical enquiry into digital interfaces, cultural geographer James Ash (2015) contends that technicity refers to the capacity for technology to give inhabitants an orientation in time, or specifically the present moment. Rejecting objective time as a universal flow and phenomenology inspired accounts of subjective time based on human consciousness, Ash (2015) argues that time is a relational outcome of sets of events rather than a field or container in which events take place. Specifically, Ash (2015, p. 62) considers the present as “secondary to a dual process of anticipation and memory which operate to set up how the present moment is experienced.” In other words, the present moment is localized to the relations between technical or digital objects.

Taking Bucher (2012) and Ash (2015) perspectives on technicity on board, it can be argued that when inhabitants enter places, their account of the present moment is localized between the objects within that place. A useful analogy is a casino, which is usually void of clocks, windows or any other objects that inform occupants of the time. When patrons enter this place they are subjected to temporal bias towards the present, shading opportunities for patrons to consider future scenarios such as collecting their winnings and exiting. The significance of Bucher (2012) and Ash’s (2015) interpretations is the implication that any digital place has a casino-esque capacity to appropriate attention by presenting a plurality of different modulations of the present moment. Alternatively put, place-making is a manifestation of a temporal power that is capable of orienting the inhabitants’ sense of time. To this end, the power in place-making is its affordance of a temporal sense of place.

A Temporal Sense of Place

A temporal sense of place is a distinct aesthetic and sensuous experience of place, under the distinct mediation of digital ICTs. It may be beneficial to articulate this in the spirit of Massey and adopt her opulent method when describing a global sense of place. With this in mind:

Imagine you are a superhuman being with a capability to travel across space/time in any given moment. You are on the bus where commuters are glued to their smartphone screens, to pass the time before they get home. Now you are at a concert, where multiple members of the audience watch through their screens to capture the moment for later future use. In a home you see a 20-something try to explain the mechanics of a new app to their 50-something parent. Across the street you bear witness to a couple’s argument centered on comments made in a messenger app several days ago. On the other side of the world in a flat is a programmer who is adjusting the code of their video blog. Upstairs is a book-worm who is lost in the words of their favorite author. Suddenly you are in an office looking over the shoulder of an employee compulsively checking their inbox to see if new emails come in. You are in the countryside watching a group of campers around a fire, sharing stories. You are following a tourist aimlessly walking, looking up whilst lost in a big city. You are seamlessly moving across space and time watching people in different places, preoccupied in the past, present or future.

The purpose of Massey’s description was to provide the reader with a global perspective on the politics of mobility or spatiality. Here the purpose is to provide a grand sense of temporal disruption, distinct from the chronological or sequential view of time that has been valorized in Western culture ever since the Enlightenment (Hassan 2012). In a hyper-mediated attention economy, this is not a politics of mobility but a politics of perception or attention. Where Massey (1991, p. 26) drew a comparison between the “jet-setting” corporate to the “refugees from El Salvador”, the comparison here is between those who have the capacity to intermediate their temporal experience and those who are (willfully or not) completely submerged in it. While Massey asked her audience for a global view of place to see access and spatial movement, here a view of place is required that unlocks attention, agency and understanding. A temporal sense of place details the flows of information, objects or stimuli that inhabitants actively perceive, which modulates the relationship between expectation and recollection, and in turn shapes the present moment. Where Massey viewed power as a force that enables or restricts movement, here it appropriates attention, shapes normative views, modifies agency, or the capacity to act and understand. In a temporal place, power manifests as the knowledge or agency to intermediate the temporal experience of oneself and/or other agents in that place. This temporal power can be wielded to either enhance or restrict inhabitants’ capacity to act, perceive and understand information in that place.

The appropriation of attention as a temporal power is not necessarily pejorative; it has been the primary objective of telecommunication, publishing, advertising and entertainment industries, education and artistry for many decades. A measure of success in these instances is often the level of which attention is held. We seek out ‘page-turning’ books and ‘escapist’ films and applaud captivating performances, speeches or engaging pedagogical methods. While such logics have traditionally been confined to a theatre or classroom, in an attention economy they have extended without reproach into all other places. Somewhere along the line, among the agglomerations of data, the proliferation of accessible information, the ubiquity of invisible computing infrastructures and the promises of increasingly immersive augmented and virtual realities, the same attention-grabbing logics within temporal power have imprinted elsewhere. This power, present in place-making creates new opportunities and risks for attention and understanding that can be utilized to realize new forms of value. However, as attention is a scarce resource, it is important to consider what types of value should be sought, which is explored in greater detail in the following two case studies.

Facebook’s Compressed Sociality

Facebook is the largest and most popular social networking service (SNS) in the world. In its second quarterly report of 2019, Facebook noted that it has over two and a half billion monthly active users across its SNS, news and entertainment services and in-application games (Hutchinson 2019). While Facebook may brand itself as a ‘social utility’, it is also a commercial advertising business, in which users are not the customer but also the product. It is, therefore, in Facebook’s interest to seek economic value by encouraging users to spend time and share data within their ecosystem.

Facebook is a social place that modulates a quantifiable temporal experience rather than a qualitative one. Rushkoff (2013) adopts an Aristotelian perspective to interpret ‘chronos’ as measurable or quantifiable time and ‘kairos’ as the opportune moment or qualitative time. As a data hungry business seeking to extract economic value, the logics and architectures of Facebook’s compute chronos while ignoring kairos. This reduces Facebook’s social experience to the digital equivalent of a public ceremony rather than an intimate get-together, which produces a highlights package of social and news events. This is epitomized in Facebook’s Year in Review service, which curates for users their most ‘significant’ moments of the past year. The significance of each moment is based on a quantifiable calculation, subject to ‘likes’, ‘tags’ or ‘shares’, as opposed to qualitative time or kairos. These services are fueled by chronos, which encourages users to internalize an events based approach to their wider social life; to take and upload more photos and videos; to send messages and ‘check-in’ to physical places. Based on this architecture there is a normative effect: only by capturing chronos can users enjoy the ‘optimal’ Facebook social experience. Similar to the ethos of search engine optimization, to be noticed in a SNS one has to understand and play to the mechanics. This leads to a social and temporal experience that is both disembodied and associative, asking frequent visitors to quantify their sociality. From this perspective, Facebook users do not share or post information for the present, but for their future.

Figure 1. Facebook Year in Review functionality (Source: Facebook)

Facebook’s temporal power has additional normative effects, which subjects its users to a homogenous and conforming social experience. Rayner (2012) argues “by making our actions and shares visible to a crowd, social media exposes us to a kind of virtual panopticon”. Similar to Foucault’s interpretation of the Panopticon, which inscribes a gaze onto the prisoners, socialites within Facebook’s walls are subjected to the power to judge. In this sense Facebook is also a ‘playground’ type of place where identity formation occurs, inscribing normative practices upon its inhabitants. In this visible place, the behavior of inhabitants resembles those of actors, who tailor their performance to the audience. Ross (2012) argues this visibility has a normative effect on behavior, in the sense that inhabitants conform their behavior when they know they are being observed. Both Rayner and Ross suggest that in visible places such as the Facebook newsfeed, inhabitants are encouraged to perform their thoughts and feelings and pander to the crowd. Psychologist Sherry Turkle (2015) raises similar concerns that digital technologies conflate various types of conversation into group-talk.

Furthermore, Facebook’s temporal power construes an unbalanced perspective on communication, with a bias towards connection. Light (2014) deconstructs SNS normative practices in his ethnographic study on disconnection. He challenges the technological deterministic view that assumes humans crave unfettered connection and describes several nuanced disconnective practices central to human communication. Light (2014) contends that Facebook coerces towards a circular use of their services, nudging users towards increased connectivity to other users within their digital ecosystem, and shading perceived opportunities to disconnect. This is supported by Karppi (2018) who contends that the taxonomy of Facebook is designed with the aim to deter users from permanently deleting their account by making the temporary disconnection options of account log-out and deactivation much more visible and accessible.

The political consequences of Facebook’s temporal power are that as a commercial platform, it could impose a monopoly on socio-temporal experience with the goal to engage users for increasingly longer, measurable and frequent periods of time. This is evident in scenarios such as music concerts where a considerable number of attendees choose to watch the entertainment through their phone. Addressing the issue of so-called “screen addiction”, spoken word artist Gary Turk (2014) produced a poignant short-video Look Up that describes the difficulties of stopping scrolling and has garnered over 62 million views on YouTube. Despite the evidence of interest in the stickiness of Facebook and other technology platforms, the popularity of Facebook continues to grow and share value rise (Hutchinson 2019). This reinforces the notion that the politics of attention appropriation should be about more than raising awareness and enabling agency.

The Disruptive Pedagogy of AfroFuturist Affair

AfroFuturist Affair (AFA) is a US grassroots organisation that celebrates and distributes AfroFuturism culture, literature, film, art and music content across multiple channels. AfroFuturism is a movement that was coined in 1994 by culture critic Mark Dery (2016) to “theorize the dystopian fiction of being black in America, and the radical politics of remembering a dismembered past”. What began as a fringe cultural movement that was “sought in unlikely places” (Dery 1994, p. 182), has grown in popularity with Hollywood actor Jada Pinkett-Smith declaring her children to be AfroFuturists. In an interview with Atlanta Blackstar (2014), AfroFuturist blogger Sherese Francis considers a purpose of the movement to: “shape minds to think outside of the boxes of…oppressive cultures”. In this sense, AFA offers an alternative to mainstream systems and technologies that present a fixed future or a restricted concept of materiality reality. Dery (2016) attributes the rise in popularity of AfroFuturism as a response to the positivist or materialist biases brought around by the Enlightenment. Rather than privileging data or other forms of scientific inquiries into various facets of the individual and society, AfroFuturism asserts an alternative model; one that is mythic, rhetorical, stylish and intertwined with nature (Dery 2016).

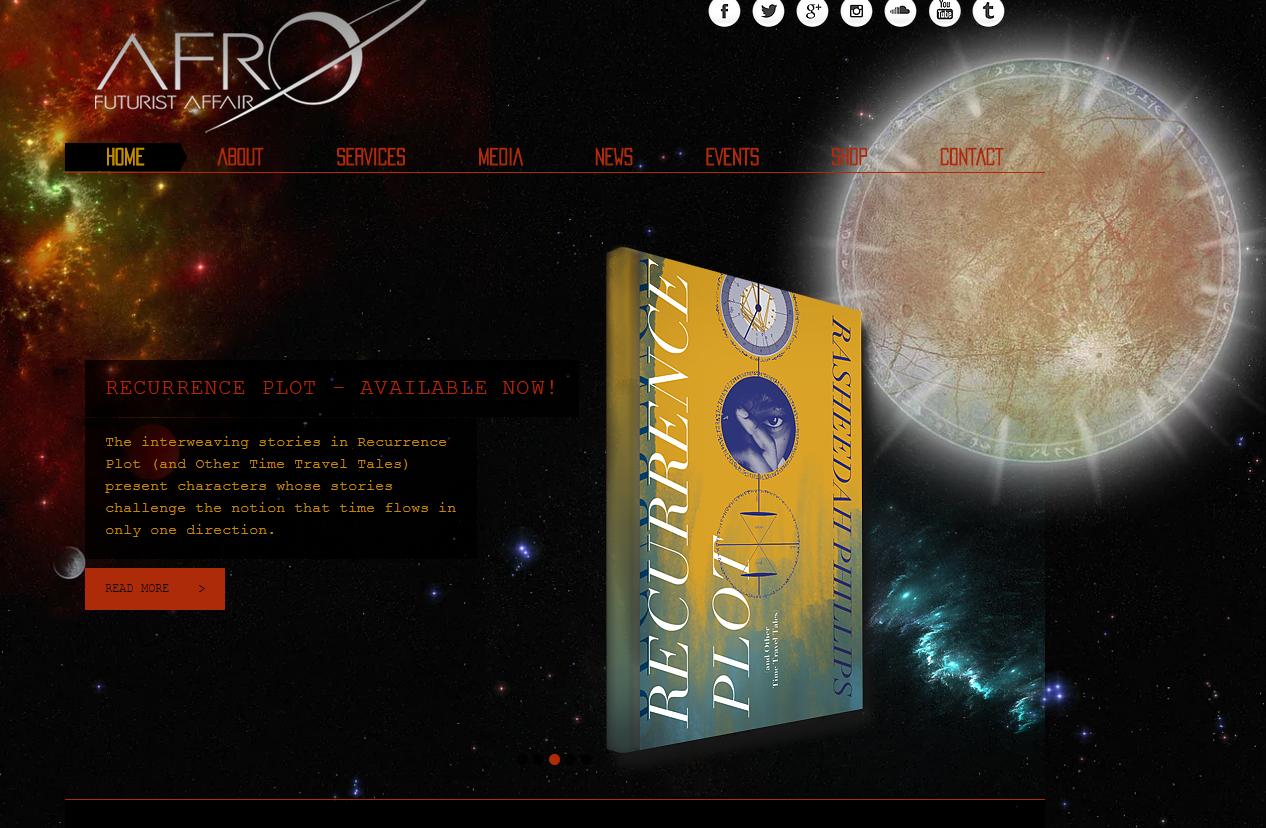

Figure 2. AfroFuturist Affair website (Source: AfroFuturist Affair)

AFA is a cross-channel place that wields a productive temporal power to disrupt entrenched and dominant pedagogical ideologies, such as Anglo-Saxon and hetero-patriarchal culture. Alternatively put, AFA is a place of information and learning that utilises temporal power to generate new forms of cultural value, seeking to break barriers and tell new stories. AFA’s content contains tools or technologies which use literature and content tropes to investigate the intersections of African Diaspora. In a piece of content called Black Quantum Fusion, editor Rasheedah Phillips (2016) collects a range of experimental writings to explore perceptions of time in relation to Black memory. Phillips (2016, p. 29) articulates the purpose of the book as exhibiting temporal agency:

under [this] intersectional time orientation, the past and future are not cut off from the present – both dimensions have influence over the whole of our lives, who we are and who we become at any particular point in space-time.

Temporal agency draws attention to one of the core tenets of information architecture: context. Wurman (2001, p. 257) asserted that understanding something new requires contextual comparison: “you only learn things relative to something you understand”. This context is, however, typically situated in a linear temporal and spatial fashion, laced with a dominant historical narrative and endowed with Western ideologies, sub-cultures and values. The aim of AFA is to disrupt this traditional linear structure and create new learning opportunities; to present non-linear temporalities that subvert typical understandings of Black culture, history and art, free from the dominant pen of the Western revisionist historian. In other words, AFA represents an alternative application of Wurman juxtaposition; a pedagogical place where learning is still underpinned by contextual comparison, but in which temporal power is deployed to question, update or replace particular contexts in order to enhance stories told by marginalized cultures.

Temporal power utilised to this effect emits a sentiment akin to critical pedagogy, a subset of education studies that questions academic canon and calls to attention the “dominant memories and repressed stories that constitute the historical narratives of a social order” (Grouix 1992, p. 101). In this sense, temporal power can connect memory and time, to effect social change. Despite her reservations about privileging temporal analysis, Massey would likely be intrigued by the political possibilities that temporal power presents. Massey’s (2005, p. 82) concerns were that any space attributed with a linear temporal dimension such as ‘developing’ were doomed on a Fukuyama-esque ‘end of history’ trajectory, with no “[room] to tell stories, or follow another path”. As temporal power can disrupt temporal linearity and subvert dominant narratives, it presents genuine possibilities to generate outward, extroverted and progressive notions of digital place.

Discussion: The Politics of Attention

So far, I have argued that a temporal sense of place is a means to articulate today’s hyper-mediated experience and framed place-making as a technology of power which appropriates attention to generate economic, social or cultural value. This presents an opportunity to address the politics specific to information architecture: the politics of attention and the implications of place-making. Information architects are agents of change and complicit in how inhabitants operate, perceive, understand and have the capacity to act within digital places. To enable this change, the practice of place-making should go beyond reducing disorientation or increasing legibility, with the addition of enabling agency. For this is not a passive politics but a politics of attention that requires the agency to perform or participate. Consider an analogy to a board game, where the baseline to participate is to be aware of and understand the rules. Similar to Resmini (2016) I consider that it is near impossible to participate when the architectures of place are black-boxed, akin to a board game where the rules are in an illegible language that frequently changes. When buildings are commissioned to be designed, future residents have active roles in the architecture process. While it is clearly not feasible to expect users to be consulted on every ambient digital place they will encounter, at the same time we should not just expect access to such places to come as a trade-off to a shaded view on reality. This is a politics of attention and not mobility. Therefore, elements of the transparency afforded in analogue design practices should carry-over to information architecture, otherwise too many users are unknowingly stepping into places that may be ill fitted to their particular choosing. Information architecture should provide instructive tools for inhabitants of digital places to understand the various means to engage and participate within them, without sacrificing temporal agency. A specific example in a news and entertainment place, offered by design ethicist Tristian Harris (2016), is disclosing the estimated time it will take to read the chosen content. Such affordances set temporal expectations while avoiding the ‘bottomless bowls’ of content that digital places such as YouTube and Facebook facilitate via endless newsfeeds and video auto-play functionality.

Further to this, information architects should design with the aim of generating a balance of economic, social and cultural values. The Facebook case study demonstrates a concern, not only with its monopolization of the socio-temporal experience, but also in that the only value worth extracting from digital places is economic. As Thrift (2005) argues, the influence of capitalism has shifted from tangibles to the world of ideas, and this is no different when the lens is turned to focus on digital environments. Without the support behind credible alternatives such as the attentional commons (McCullough 2013; Crawford 2016) there is a risk that most digital places become fertile grounds for what has been classified as cognitive capitalism (Peters et al 2011; Boutang 2012) or surveillance capitalism (Zuboff 2019) where the explicit aim is to create economic value at the cost of modulating user attention. In this sense, place-making is at risk of being complicit in capitalism’s domestication of digital places (McChesney 2013) or more specifically, the unchecked mining of user attention, which is, in effect, the premium commodity in short supply. As studies develop and we learn about the long term consequences of being subject to ubiquitous connectivity, new alternatives may emerge. However, I share concerns with Light (2014) that in a dominant capitalistic culture without credible alternatives, disconnection may be something we have to pay for.

A tempting conclusion is to adopt the provocative overtones of Karl Marx or David Harvey concerning capitalism to claim that place-making annihilates time. But this would be unnecessarily alarmist, undermine user agency, and privilege digital information communication tools (ICTs) by ignoring the numerous ways that historical ICTs have consumed and regurgitated temporality in different ways. Plato (1952 [340BC]) famously detested the effects of writing on oral culture and the capacity to memorize information, yet by capturing the thoughts and experiences of authors in concrete from, writing arguably paved the way for print and academia culture. Media scholar Neil Postman (1985) criticized electrical telegraphy for decontextualizing information and creating the news commodity, yet it allowed information to travel beyond the speed of a human being (and the steam engine train) to reach new audiences. Digital place-making may disrupt the pre-digital normalized temporal experience but provides distinct new possibilities to share information, tell stories and otherwise communicate to one another. As the AfroFuturist Affair (AFA) case study demonstrates, the temporal power present in place-making can be used productively to generate cultural and social value, morph perceptions and challenge norms to meet desirable ends. Similarly to Massey’s sentiment for her beloved London suburb Kilburn, it is possible to be optimistic and progressive about the opportunities that a temporal sense of place presents.

With the emergence of immersive technologies like augmented and virtual reality, it is inevitable that issues relating to the attention economy will continue to be scrutinised and I therefore consider future research on agency, embodiment, ambient technologies and the attention commons to be of critical importance. My hope is that identifying information architecture and place-making as a political practice will spur further researchers, academics and practitioners to critically assess their role as information architects and question what sort of digital world they want to influence and be a part of going into the future.

References

- Arango, J. (2011) Architectures. Journal of Information Architecture. Vol. 3. No. 1. Pp. 45–53. https://journalofia.org/volume3/issue1/04-arango/.

- Ash, J. (2015) The Interface Envelope: Gaming, Technology and Power. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Atlanta Blackstar (2014) Using Afrofuturism to Power New Modes of Tech – Interview with Blogger Sherese Francis (Futuristically Ancient). http://blerds.atlantablackstar.com/2014/08/28/using-afrofuturism-power-new-modes-tech-interview-afrofuturist-blogger-sherese-francis-futuristically-ancient/.

- Behrent, M. C. (2013) Foucault and Technology. History and Technology. Vol. 29. No. 1. Pp. 54–104.

- Benyon, D. (2014) Spaces of interaction, places for experience. Morgan & Claypool.

- Boutang, Y. M. (2012) Cognitive Capitalism. Polity Press.

- Bucher, T. (2012) A Technicity of Attention: How Software ‘Makes Sense’. Culture Machine. No. 13. https://culturemachine.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/463-1025-1-PB.pdf.

- Crawford, M. (2016) The World Beyond Your Head: How to Flourish in an Age of Distraction. Penguin Books.

- Crogan, P. and Kinsley, S. (2012) Paying Attention: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy. Culture Machine. No. 13. https://culturemachine.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/463-1025-1-PB.pdf .

- Dery, M. (1994) Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. Duke University Press.

- Dery, M. (2016) Afrofuturism Reloaded: 15 Theses in 15 Minutes. http://www.fabrikzeitung.ch/afrofuturism-reloaded-15-theses-in-15-minutes/.

- Fogg, B. J. (2001) Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Foucault, M. (1991) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Penguin Books.

- Greenfield, A. (2006) Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing. New Riders Publishing.

- Grouix, H. A. (1992) Border Crossings: Cultural Workers and the Politics of Education. Psychology Press.

- Hassan, R. (2012) The Age of Distraction: Reading, Writing, and Politics in a High-Speed Networked Economy. Transaction Publishers.

- Harris, T. (2016) How Technology Hijacks People’s Minds —from a Magician and Google’s Design Ethicist. Medium. https://medium.com/swlh/how-technology-hijacks-peoples-minds-from-a-magician-and-google-s-design-ethicist-56d62ef5edf3#.sf8cwtw9j.

- Hinton, A. (2015) Understanding Context: Environment, Language, And Information Architecture. California: O’Reilly Media.

- Hui, Y. (2012) What is a Digital Object? Metaphilosophy. Philoweb: Toward a Philosophy of the Web (special issue). No. 4. Pp. 380–395.

- Hutchinson, A. (2019) Facebook Posts Strong Revenue Result in Q2, MAU Increases to 2.4 Billion. Social Media Today. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/facebook-posts-strong-revenue-result-in-q2-mau-increases-to-24-billion/559473/.

- Karppi, T. (2018) Disconnect: Facebook’s Affective Bonds. University of Minnesota Press.

- Kelly, K. (2009) Triumph of the Default. Technium. http://kk.org/thetechnium/triumph-of-the/.

- Leach, N. (2009) Architecture or Revolution? https://neilleach.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/architecture-or-revolution.pdf.

- Light, B. (2014) Disconnecting with Social Networking Services. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Maggi, R. (2014) Toward a Semiotics of Digital Places. In Resmini, A. (ed) Reframing Information Architecture, Cham: Springer International Publishing, Pp. 85–102.

- Manaugh, G. (2007) Without Walls: An Interview with Lebbeus Woods. Bldgblog. http://www.bldgblog.com/2007/10/without-walls-an-interview-with-lebbeus-woods/.

- Massey, D. (1991) A Global Sense of Place. Marxism Today. Pp. 24–29.

- McCullough, M. (2013) Ambient Commons: Attention in the Age of Embodied Information. The MIT Press.

- McChesney, R. W. (2013) Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy. New Press.

- Peters, M. A., Bulut, E. and Negri, A. (2011) Cognitive Capitalism, Education, and Digital Labor. Peter Lang.

- Plato (1952) Phaedrus. Cambridge University Press.

- Postman, N. (1985) Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Viking Penguin.

- Rabinow, P. (1991) The Foucault Reader: An Introduction to Foucault’s Thought. Penguin Books.

- Rayner, T. (2012, June 21) Foucault and social media: life in a virtual panopticon. Philosophy for Change. https://philosophyforchange.wordpress.com/2012/06/21/foucault-and-social-media-life-in-a-virtual-panopticon/.

- Resmini, A. & Rosati, L. (2011) Pervasive Information Architecture: Designing Cross-Channel User Experiences. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Resmini, A. (2016) The Ethics and Politics of Information Architecture. 17th ASIS&T Information Architecture Summit. http://www.slideshare.net/resmini/the-ethics-and-politics-of-information-architecture

- Ross, J-M. (2009) The Digital Panopticon. http://radar.oreilly.com/2009/05/the-digital-panopticon.html.

- Rosenfeld, L. and Morville, P. (1998) Information architecture for the World Wide Web (1st ed). O’Reilly Media.

- Rushkoff, D. (2013) Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now. Penguin Group.

- Simondon, G. (2016 [1958]) The mode of existence of technical objects. Univocal Publishing.

- Thrift, N. (2005) Knowing Capitalism. SAGE Publications.

- Turk, G. (2014) Look Up. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7dLU6fk9QY.

- Turkle, S. (2015) Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. Penguin.

- Wurman, R. S. (1989) Information Anxiety. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group.

- Wurman, R. S. (2001) Information Anxiety 2. Que.

- Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Struggle at the New Frontier of Power. Profile Books.

Footnotes

[1] “A Temporal Sense of Place” is based on Alex Beattie’s MA dissertation work, completed in 2016.

[2] Scholars across the humanities contend what users trade is their attention. For a comprehensive overview on the attention economy, see Crogan, P. & Kinsley, S. (2012) Paying Attention: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy. Culture Machine. Vol. 13. https://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/view/463.

[3] For a comprehensive discussion of the shift in Foucault’s thinking in relation to technology, power/knowledge and techniques of power, see Behrent (2013).

[4] Ontological inquiries are not alien to information architecture, rather, it could be argued that the discipline arose from innovative ontological deconstructions of the information unit. Wurman (1989) offered a wealth of aphorisms about understanding the essence of information, while Rosenfeld & Morville (1998) recognized that the key to the ontology of the internet was to map the relationship between discrete informational objects such as web pages.