Laura Downey & Sumit Banerjee

Building an Information Architecture Checklist

Encouraging and Enabling IA from Infrastructure to the User Interface Architecture

Abstract

Government environments often have prescribed complex processes for obtaining and implementing technology solutions. In order to encourage and enable information architecture (IA) in government systems, it is essential to embed IA within the current processes and to view IA as part of the overall architectural framework. The definition of IA used here is broad and inclusive spanning applications, the Web and the enterprise. A common focus exists aimed at organizing information for findability, manageability and usefulness, but the definition also includes infrastructure to support organization of information. This case study describes the development of an IA checklist in a large United States government agency. The checklist is part of an architectural review process that is applied 1) during assessment of proposed information systems projects and 2) design of solution recommendations before system implementation.

Introduction: Defining Information Architecture

Defining information architecture is an exercise many researchers and practitioners have performed (Zachman 1987; Wurman 1997; Rosenfeld 2002; Bailey 2002; Dillon 2002; Toms 2002; Evernden & Evernden 2003; Dillon & Turnbull 2005; Rosenfeld & Morville 2006; Stiglich 2007; Hinton 2009). Rosenfeld (2002) noted that a widely accepted definition of IA does not exist. Dillon and Turnbull (2005) report that no formal definition of IA has been agreed upon. That still appears true today.

Several definitions in the IA field generally focus on organizing information via mechanisms such as labeling, structuring, chunking, and categorizing in order to support navigation, findability and usefulness. Bailey’s (2002) definition of IA is perhaps the simplest and most straightforward:

IA is the art and science of organizing information so that it is findable, manageable and useful. There is also a perspective from enterprise architecture that views information architecture as an enterprise wide activity that includes such aspects as data architecture, metadata management and knowledge management (Stiglich 2007).

The Association for Information and Image Management (AIIM) does not use the term information architecture but rather the phrase information organization and access (IOA). AIIM’s perspective spans application, web and enterprise levels. IOA involves preparing and accessing information.

Another definitional approach is that of Big Architect (strategic) or Big IA and Little Architect (tactical) or Little IA (Morville 2000; Dillon 2002; Dillon & Turnbull 2005). Dillon (2002) and Dillon and Turnbull (2005) discuss these competing views. Little IA and Big IA both focus on information organization with Little IA being done from the ground up and Big IA being approached from the top down. A major difference is that of user experience. Little IA does not focus on formal user experience but more on metadata and controlled vocabulary. Big IA, as the name implies, is approached from a wider view and includes user and organizational aspects with an emphasis on information being useful, usable and acceptable.

In January 2010, Forrester Research, Inc. published a report on information architecture in which IA is divided into user experience IA (application or web site level) and enterprise IA (Leganza 2010). The terms micro and macro IA are also used. The Forrester report is focused on enterprise IA. This sparked yet another discussion in the IA community.

While there are different definitions, what can be agreed upon is that IA is foundational in this information rich era. Foundational implies supporting an extended perspective.

The definition used in this paper is based upon the belief that IA is foundational and also critical for both users and organizations. User experience must be addressed and enabled at all levels. IA can be approached from the bottom up and/or the top down. IA may be applied to an application, a Web site, or the enterprise. Taking a cue from the enterprise architects, we also believe infrastructure must be addressed in order to lay the foundation for good IA. Bringing all these aspects together and building upon Samantha Bailey’s (2002) simple definition of IA, our definition of IA is:

Organization of information to support findability, manageability and usefulness from the infrastructural level to the user interface level.

This expansive and comprehensive definition allows us to leverage current established architectural practice to ensure IA is thought about and planned for in the system development process. Our approach is an IA checklist that is part of an architectural review process. The architectural review process is discussed in the next section. Following that, a section on building the IA checklist is presented. Versions of the IA checklist are included as well as discussion on the topics and questions included in the checklist. The final two sections of the paper are a description on embedding the IA checklist in a current organizational process and a summary.

Checklists and Architectural Reviews

Checklists are a mechanism for reminding and/or prompting attention to issues or topics. A checklist can be general (e.g., outlining the steps in a process so steps are not missed), or specific (listing detailed items to be addressed). A checklist is not a set of deliverables to choose from, but it can lead to discussion and consideration of deliverables.

We examined literature in IA, usability and information systems but did not find reference to IA checklists. We searched IA and usability web sites. No IA checklists were found. However, we did find mention of a few IA checklists via general web searches. These IA checklists either cover the process of performing IA activities on a project (Reith 2003) or are specific to actually designing or reviewing the design of IA (Commonwealth of Australia 2008; European Commission 2010; Deacon 2008; Borysowich 2009). The checklists of the Commonwealth of Australia (2008), Deacon (2008), and the European Commission (2010), are specific to website design. Borysowich (2009) offers a checklist for generally designing IA.

The identified checklists focus more on process, design, and design review - and do not include issues of infrastructure, platform, services, technology, policy, and standards. We would like to note however that Morville and Callender (2010, p. 35-6) start to address some of these aspects with respect to an informal search checklist. Example topics include system architecture, performance, access control, relevance tuning, federated search and analytics.

In the software engineering world, checklists are a standard part of architectural reviews (Maranzano, Rozsypal, Zimmerman, Warnken, Wirth & Weiss 2005). Architectural reviews are best practices that help organizations find design problems early, manage and leverage software and hardware infrastructure, identify technology gaps, and enable the best and most productive use of an organization’s assets, including information. Architectural reviews are routinely performed across a variety of corporations and organizations. Maranzano et al (2005) report that since 1988, they have collectively performed over 700 architectural reviews across their four companies - AT&T, Avaya, Lucent, and Millennium Services.

A key component of the architecture review is the architectural checklist. An architectural checklist usually takes the form of a set of questions (Maranzano et al 2005; Borysowich 2005). The questions are designed to remind reviewers of pertinent areas and specific issues to be addressed during systems design. Reviewers use checklists to examine proposed and existing systems and highlight missing or conflicting design elements as well as to suggest ways in which systems will be aligned with current and future planned architectures.

In our organization, we have a “solutions” architecture checklist that covers the essential concerns of information system architectures. The solutions checklist is based on a layered, service oriented, reference architecture that helps align the solutions with the organization’s mission. The reference architecture that is used focuses on sharing the enterprise level information and business functions throughout the enterprise. In formulating a solution based on the reference architecture, it became clear that information generation, delivery, consumption and governance are architecturally significant concerns that need to be addressed by the solution architectures. This demanded that IA be considered alongside other system architectural concerns.

Our goal in designing the IA checklist as part of the architectural review process was to create a set of questions that gets people thinking about and discussing IA in terms of infrastructure, existing technology, services, and platform across the enterprise as well as information generation, delivery, consumption and governance in order to lay the foundation that can then be fully exploited and realized at the user interface level. This broad perspective encourages a collaborative approach to an IA solution. Morville and Rosenfeld (2006) mention technology assessment as part of the IA research process and that it is important for information architects to engage information technology professionals. An IA checklist provides a formal opportunity for this engagement and collaboration.

The IA Checklist: Building the Checklist

The initial draft of the IA checklist was based on 1) AIIM’s IOA perspective because it offers a broad approach and, 2) the significant experience of a senior information technology specialist with a background in information architecture, usability, and computer science. The major concepts of IOA (AIIM 2008, p. 12) are:

-

Preparing and organizing information

- Architecture - structure and composition of a repository, information collection or individual document

- Intelligence - enriched content (i.e., metadata, categorization)

-

Accessing information

- Search and Retrieval - querying information and obtaining matching results

- Findability - quality of being locatable or navigable

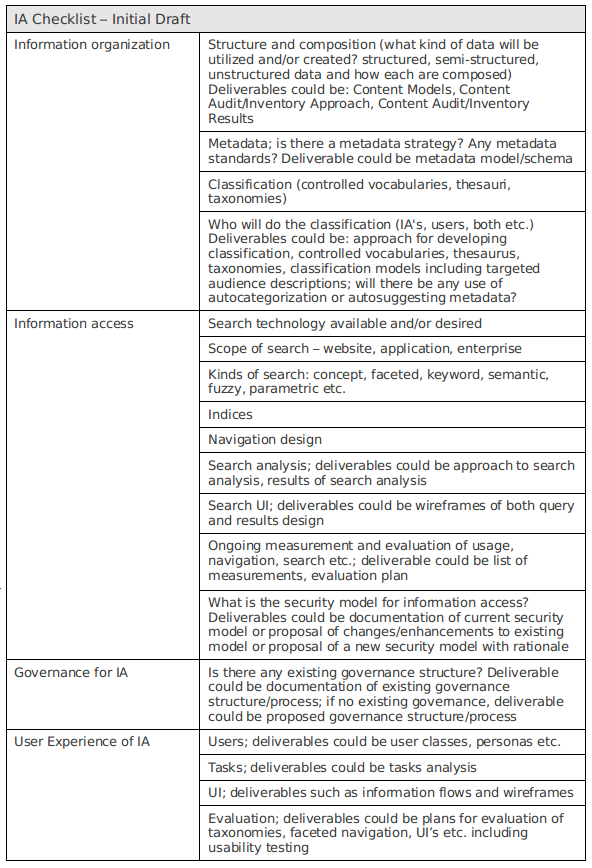

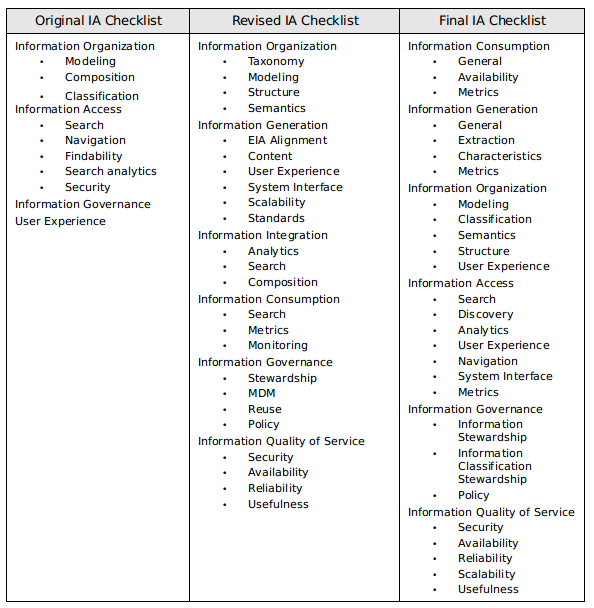

Figure 1 shows the first draft of the annotated checklist. It included four major areas: information organization, information access, governance, and user experience. The initial checklist also contained specific questions and items in those four areas, as well as examples of associated deliverables. Organization of information includes structure, metadata and classification. Access covers search and navigation, including choice of search technology. Governance deals with maintenance and change control of IA. User experience deals with user research and usability of IA elements.

The IA checklist was originally targeted more towards the planning and implementation phases of an approved project. The idea was to make sure IA was adequately addressed and handled during system design and development.

After a meeting with the traditional system and software architecture team, it became clear that we wanted to address IA at the earliest time possible and also from the infrastructure level through the user interface level. What was missing from the original IA checklist was the infrastructural dimension - looking at IA from an enterprise architecture and system architecture perspective.

Figure 1. Initial Draft of IA Checklist

So we began looking at how to embed IA into the current architectural review process and using the pattern of checklists already established for solution architecture reviews. We took elements from the initial draft of the IA checklist and elements from an existing solutions architecture checklist and produced a new outline for the checklist which is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Revised Draft of IA Checklist

The revised draft did not include deliverables because the aim was to examine what areas and issues of IA were being addressed during a review of a proposed/existing system, not artifacts and “how” things were being addressed. Building upon the foundational theme, we included areas of information generation, consumption and integration as well as standard architectural elements such as governance and quality of service. Information generation refers to what information a system will produce for its own use and for use by other systems. Correspondingly, consumption refers to what information a system will consume from other systems. We considered integration as a separate area but later decided against it since the subareas of integration (from an IA perspective) could be easily categorized in other major areas. We also viewed technology integration as the purview of system architecture and not IA.

During several iterations of the IA checklist, we added and adjusted questions as well as re-arranged the areas and subareas to reflect what we deemed a logical categorization and order. We also produced a very high level set of questions to occur during a quick, cursory review of a proposed project. This is Part 1 of the IA checklist and coordinates with our internal review and approval process discussed in the next section of this paper (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Final IA Checklist - Part 1 - High Level Questions

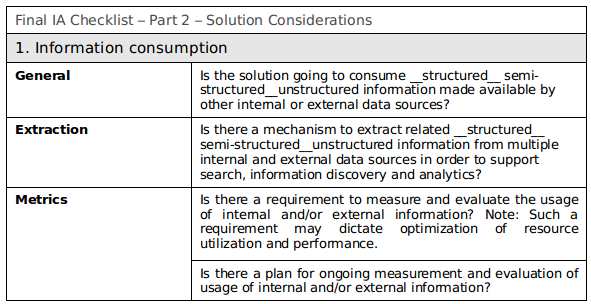

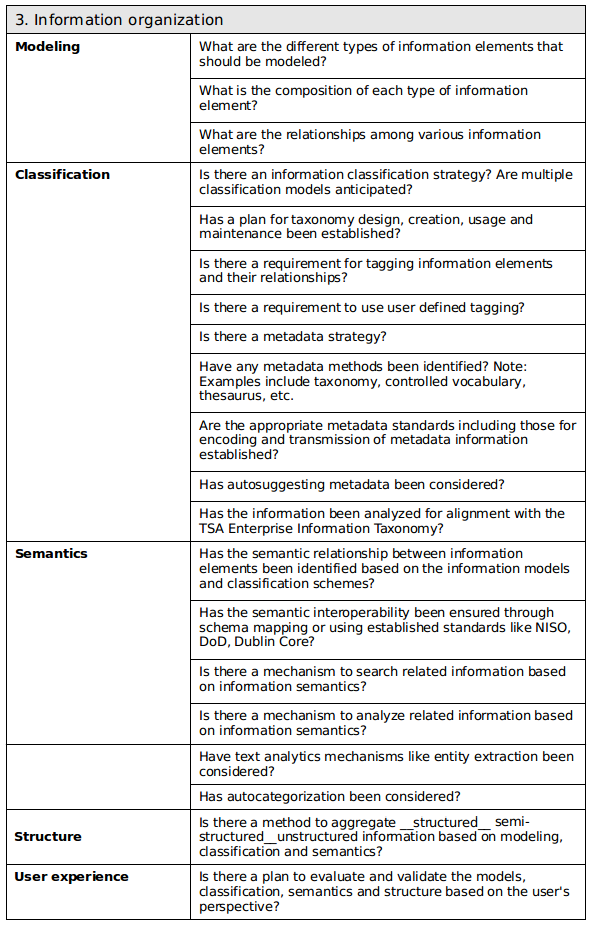

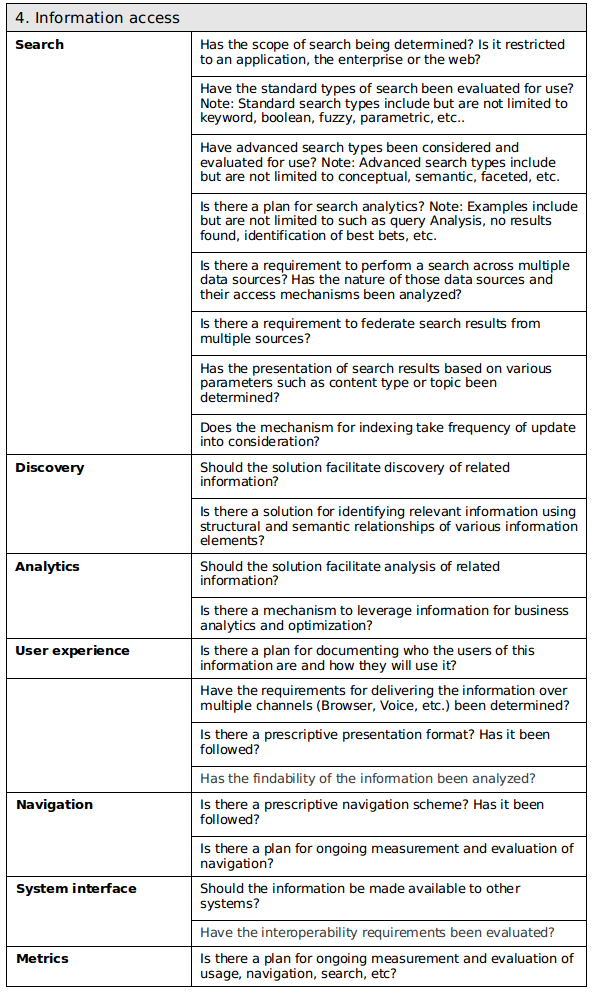

Part 2 of the IA checklist is the set of questions used to review a project that has been approved and has a statement of work (SOW) or that has asked for an IA review (fig. 4). Part 1 questions roughly correspond to the major areas of Part 2.

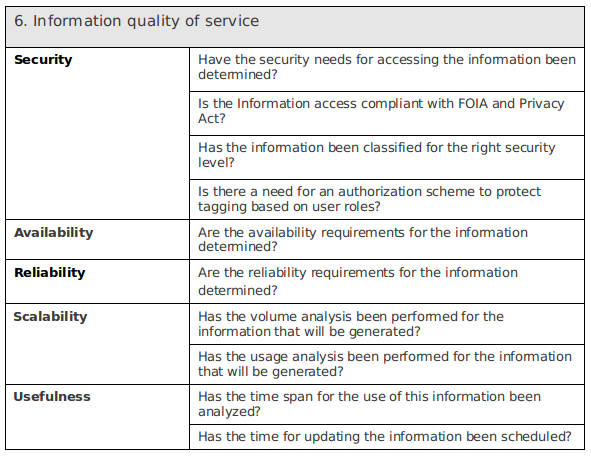

The major areas of part 2 of the checklist are: information consumption, information generation, information organization, information access, information governance, and information quality of service. Part 2 of the IA checklist is organized as a set of solution characteristics and considerations. This follows the pattern of other architectural review checklists used in our organization.

Weaving the ideas from the original IA checklist with the more traditional perspective of an architectural checklist was both interesting and a challenge. Arrangement of the checklist categories as much like a traditional card sort activity with different perspectives offering different categorization schemes. Each approach brought something to the table. We believe the final results bridge the different definitions of IA as well as the IA perspective and the enterprise architecture and system architecture perspectives.

Figure 5 provides a comparison of the major areas and subareas from the original IA checklist, the revised draft of the IA checklist, and the final IA checklist. This shows the evolution of the checklist. The original IA checklist was composed by an information architect. The revised draft was composed by a system architect after presentation of the initial IA checklist and discussion. The final checklist is a result of much discussion, explanation and negotiation.

Figure 4. Final IA Checklist, Part 2: Solution Considerations

Figure 4. Final IA Checklist (cont.)

Figure 4. Final IA Checklist (cont.)

Figure 4. Final IA Checklist (cont.)

Figure 4. Final IA Checklist (cont.)

Figure 4. Final IA Checklist (cont.)

Figure 5. Comparison of areas/subareas of different iterations of IA checklist

Final Checklist: Discussion

The categories of generation and consumption reference a foundational notion of IA in terms of what information a system will generate and/or consume. Structure of information is a key consideration so associated questions were included to address the generation and consumption of structured, semi-structured and unstructured data. Composition of data drives different information architecture solutions as well as technology choices. Additionally, identifying internal and external systems is important since an organization has control over internal systems and little control over external systems.

Organization and access are areas that are familiar to information architects covering modeling, classification, structure, metadata, semantics, search, navigation, analytics, and user experience. Three key aspects are emphasized: classification, semantics and search. Classification is a major mechanism for organizing information so it can be comprehensively understood and utilized. Semantics and semantic technology are key components given discovery requirements and providing a way to leverage technology and to exploit information relationships. Considerable attention is also given to search since it is a major and expected feature in systems. Questions on search scope, types of search, search analytics, data sources to be searched and presentation of search results are included. Understanding indexing requirements as well as different search requirements drives services and technology choices. It is important for both IA’s and engineers to understand and discuss these kinds of issues (Morville & Callender 2010).

Governance involves stewardship of information and stewardship of information classification (e.g. changes to metadata or taxonomy) as well as any information policy. Information policy is important to address in terms of how information is handled and who is allowed access. Government organizations often have detailed information policies associated with specific information types such as handling of secure sensitive information or personally identifiable information. Quality of Service is a standard architectural area that covers security, availability, reliability, scalability and usefulness - again supporting the foundational notion of IA.

Metrics are a recurring theme throughout the IA checklist because measurement provides information for volume planning as well as providing usage statistics, search statistics, and measures of success. Questions on strategy (i.e., metadata strategy) are a way to get system designers and customers to think about IA from a strategic perspective. Rosenfeld and Morville (2006, p. 265) reference key technology integration areas as part of an IA strategy. These areas are: search engines, content management, auto-classification, collaborative filtering, and personalization. References and questions on standards in the checklist are included to coordinate with other systems (e.g., a system using Dublin Core as a metadata standard) and to address any compliance issues.

Taken all together, the areas, subareas and associated questions of the final IA checklist provide a comprehensive framework in which to drive and assess information architecture of a proposed or existing system. While this paper reports on embedding the IA checklist in an architectural review process, the content of the checklist is not specific to any particular process - it is specific to IA needs and issues. Therefore, the IA checklist could be utilized in other system development processes, preferably as early as possible in the system lifecycle, to effectively address user and organization needs as well as influence architecture and technology choices. The final step in realizing the benefit of the IA checklist is to embed it in current organizational processes. This is discussed in the next section.

Embedding the IA Checklist in an Organizational Process

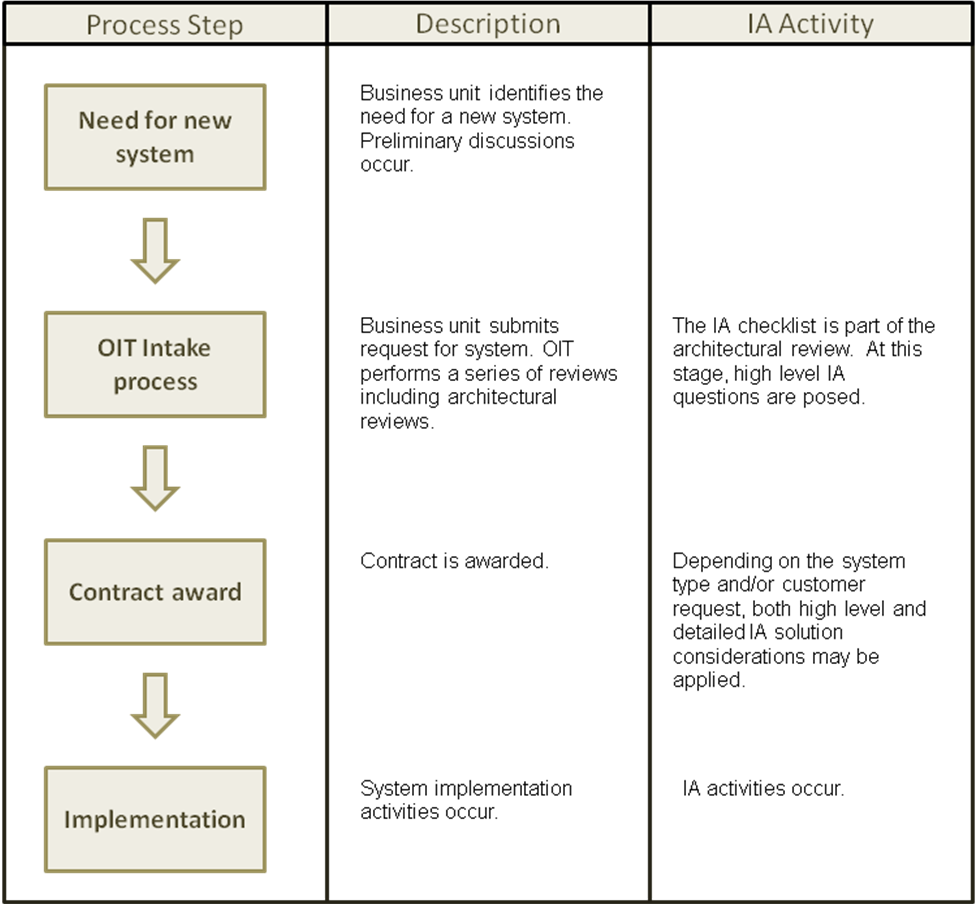

Government environments often have prescribed complex processes for obtaining and implementing technology solutions. The Office of Information Technology (OIT) at the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has an existing process for initiating and implementing information systems. At the highest level, the process includes four steps: Business unit identifies need for new information system; OIT Intake process; Contract award; Implementation.

Figure 6. High level process showing where the IA checklist is applied.

There are other steps and sub processes associated with the overall systems lifecycle such as detailed acquisition steps and processes, and technology and approach evaluations. But the goal here is to show where the IA checklist fits. For simplification purposes only the major relevant steps and associated activities have been presented in Figure 6.

After a TSA business unit identifies the need for a new system, it submits that request to OIT. OIT then performs a series of reviews to ensure OIT concerns and requirements have been met. The intake process includes reviews by different departments covering aspects such as infrastructure, software and hardware, security and architecture. The architectural review looks at issues regarding: application architecture, data management, and information organization and access (IOA). The IA checklist fits into the IOA portion of the review. The architectural review can be at a high level (Part 1 of the IA checklist) or more detailed (Part 2 of the IA checklist) depending on the system and/or requests from the customer.

Envisioning Use of the IA Checklist

The IA checklist presented has not yet been applied. Near future plans include utilizing the IA checklist and gathering feedback for improvement purposes. In this section we briefly describe our vision for applying the checklist.

There are two opportunities to make use of the IA checklist in the referenced development process. At a minimum we envision use of Part 1 of the IA checklist as a trigger to get stakeholders, architects and developers thinking in terms of IA needs and issues during systems development. If a system is identified as having a heavy need for IA and related issues to be addressed, then Part 2 of the checklist will be applied to address in detail the architectural considerations of: information generation, information consumption, information organization, information access, information governance, and information quality of service.

Impact to the development process will be minimized to the extent that the IA review is included in the existing architectural review process. The review occurs early on so as to emphasize IA needs and potentially avoid costly re-designs resulting from lack of identification of important information needs. The potential benefits to users and the organization are systems that include better organized information to support findability, identification of connections in information, and ultimately actionable decision making.

Summary

The internet, e-commerce, organizational interdependencies, knowledge management and systems thinking have helped drive the view of information as a critical organizational asset (Evernden & Evernden 2003). With this recognition of information criticality, it naturally follows that IA has broadened and increased its role in the organization. This will only continue with 1) the amount of information being generated and consumed, and 2) further development of technologies aimed at making sense of information spaces - so that the right information can be delivered at the right time to the right people.

Many definitions of IA exist. We offer the following:

Organization of information to support findability, manageability and usefulness from the infrastructural level to the user interface level.

This definition is aimed at emphasizing the scope of IA in today’s information laden environments. With an expanded scope, IA needs to be included as a major component of architectural planning and assessment. Doing so enables IA to be addressed from the enterprise architecture and system architecture perspective so that IA is supported and considered at all levels.

One way to embed IA in the systems lifecycle is to incorporate IA into the architectural review process via a checklist. An IA checklist helps remind system designers and customers to account for, and plan for, IA in their system. By placing IA in the context of an overall architectural framework - it puts IA on the same footing as other architectural concerns instead of a “nice to have” or an afterthought. An IA checklist helps designers and engineers engage and communicate about user needs and to select the appropriate solutions given technology, organization and/or cost constraints (Morville & Callender 2010). Further, an IA checklist highlights technology integration issues that are part of the IA strategy (Rosenfeld & Morville 2006).

In order to encourage IA from the infrastructural level through the user interface level, it is essential to view IA as part of the overall architectural framework and to embed IA into current organizational processes that deal with system development and implementation. This approach supports the expanded scope and foundational notion of IA and embeds IA into an existing and credible process.

References

- Association for Information and Image Management (AIIM). (2008) IOA Workbook 1: Practitioner Level, Washington, DC: AIIM.

- Bailey, S. (2002) Do you need a taxonomy strategy? Inside Knowledge, 5(5). http://www.ikmagazine.com/.

- Borysowich, C. (2005) Observations from a tech architect: enterprise implementation issues and solutions. Toolbox for IT. http://it.toolbox.com.

- Borysowich, C. (2009) Checklist for designing information architecture. Toolbox for IT. http://it.toolbox.com.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2008) Better practice checklist - 15. information architecture for websites. Department of Finance and Deregulation, Australian Government Information Management Office. http://www.finance.gov.au/e-government/better-practice-and-collaboration/better-practice-checklists/information-architecture.html.

- Deacon, D. (2008) Information Architecture: Tasks and Tools for Improving Your Web Design.

- Dillon, A. (2002) Information architecture in JASIST: just where did we come from? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(10), 821-823.

- Dillon, A. and Turnbull, D. (2005) Information architecture. In Drake, M. (ed) Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science: First Update Supplement. Taylor & Francis.

- European Commission (2010) Information architecture. Information Provider’s Guide: The EU Internet Handbook. http://ec.europa.eu/ipg/plan/inf_archit/index_en.htm.

- Evernden, R. and Evernden, E. (2003) Third-generation information architecture. Communications of the ACM, 46(3), 5-8.

- Hinton, A. (2009) The Machineries of Context, Journal of Information Architecture, Vol. 1. Iss. 1.

- Leganza, G., Cullen, A., Karel, R. and An, M. (2010) Topic overview: information architecture. Forrester Research.

- Maranzano, J.F., Rozsypal, S.A., Zimmerman, G.H., Warnken, G.W., Wirth, P.E. and Weiss, D.M. (2005) Architecture reviews: practice and experience. IEEE Software, 34-43.

- McKnight, W. (2007) Responsibilities of the information architect. Ask the Data Management Expert: Questions & Answers. http://searchdatamanagement.techtarget.com.

- Morville, P. and Callender. J. (2010) Search Patterns. O’Reilly.

- Morville, P. (2000) Strange connections. Argus Center for Information Architecture. http://argus-acia.com/strange_connections/strange004.html.

- Reith, T. (2003) IA Checklist. http://www.treith.com/ia_presentation/2downloads.html.

- Rosenfeld, L. (2002) Information architecture: looking ahead. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(10) 874-876.

- Rosenfeld, L. and Morville, P. (2006) Information Architecture for the World Wide Web (3rd ed). O’Reilly.

- Stiglich, P. (2007) Data architecture vs. information architecture. Ask the Data Management Expert: Questions & Answers.

- Toms, E. G. (2002) Information interaction: providing a framework for information architecture. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(10), 855-862.

- Wurman, R.S. (1997). Information Architects. Graphis Press.

- Zachman, J.A. (1999) A framework for information systems architecture. IBM Systems Journal, 38(2-3), 454-470 (a reprint of 1987 version).